Ákos Birkás: A Human Being is Always Interesting

28 november 2023 – 26 january 2024

A concise part of Ákos Birkás’ oeuvre, which came to the end with the artist’s death in 2018, is on view for the first time at Vintage Galéria, selected by the Ákos Birkás Art Foundation. The joint aim of the foundation and the gallery is to research and introduce the oeuvre of Ákos Birkás to the Hungarian and international public, the current exhibition is also part of the work in progress.

Ákos Birkás’ painting career started in the mid-1960s with small-scale, existentialist portraits, most of which he later destroyed. The self-portraits, which are painted in a pastiche style, attempting abstraction through an expressive – according to Birkás, “overpainted” – painting method, are documents of a self-seeking young artist who wanted to keep distance from both the learned and expected style, traditions and modernism (Self-Portrait, late 1960s). His self-defining painterly and personal attempts remained unrecognized at the time, but in retrospect, they can be compared to the contemporary efforts of other “maverick” artists (e.g. Frank Auerbach).

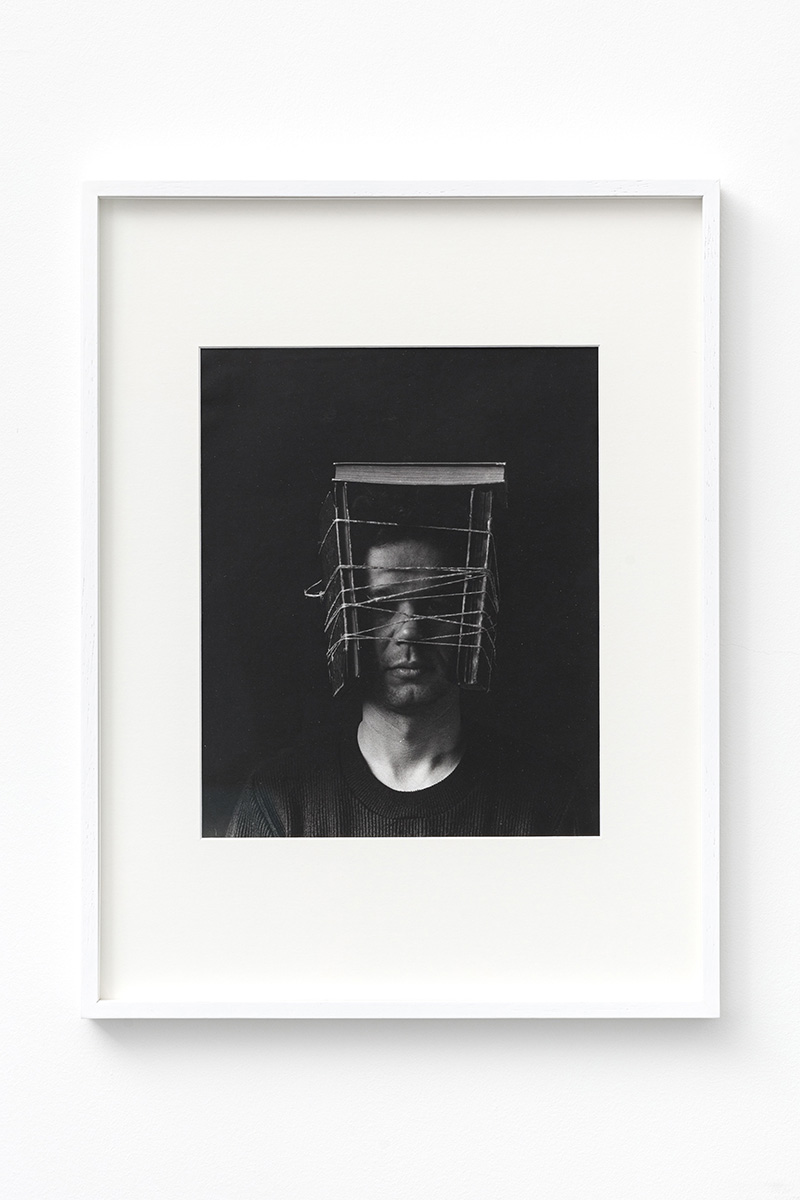

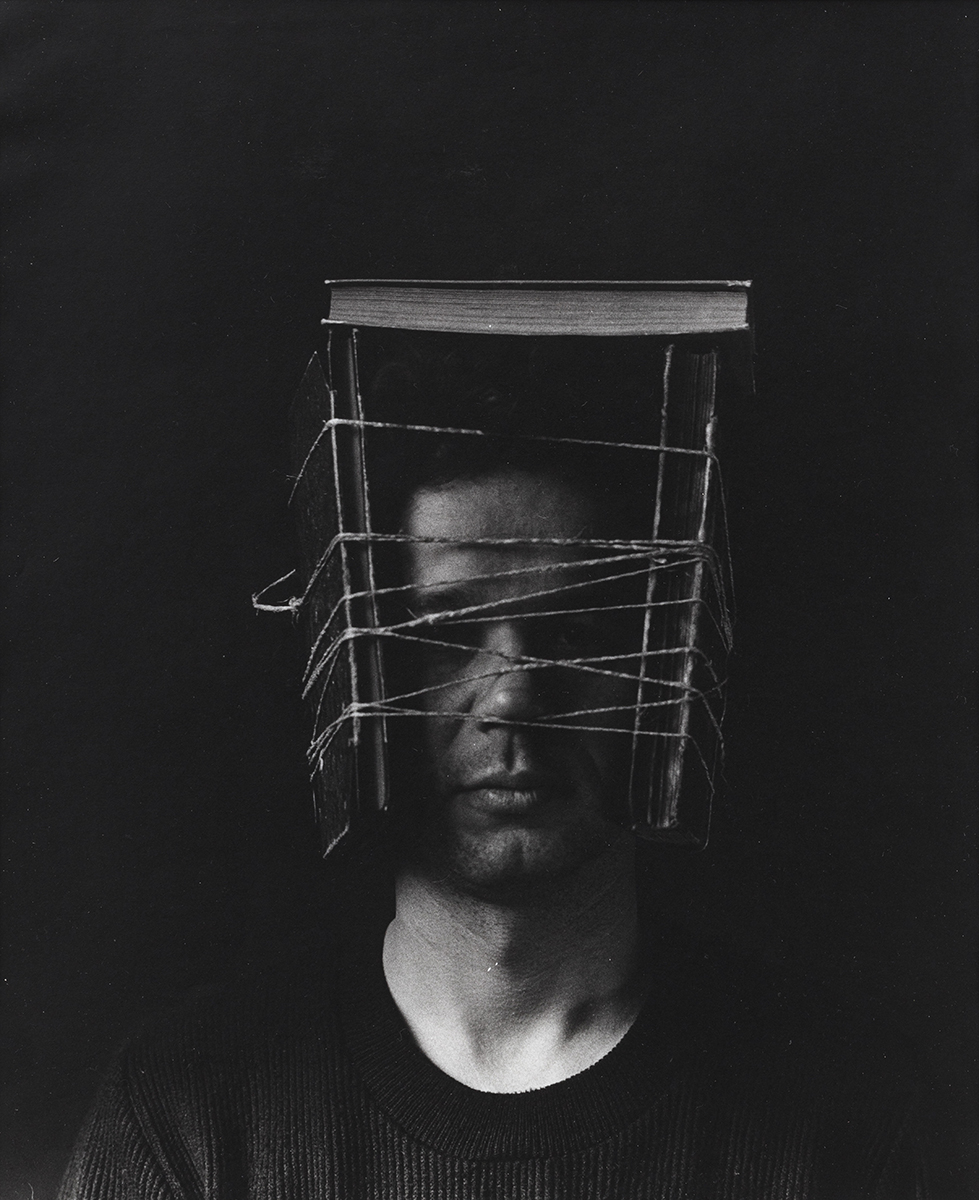

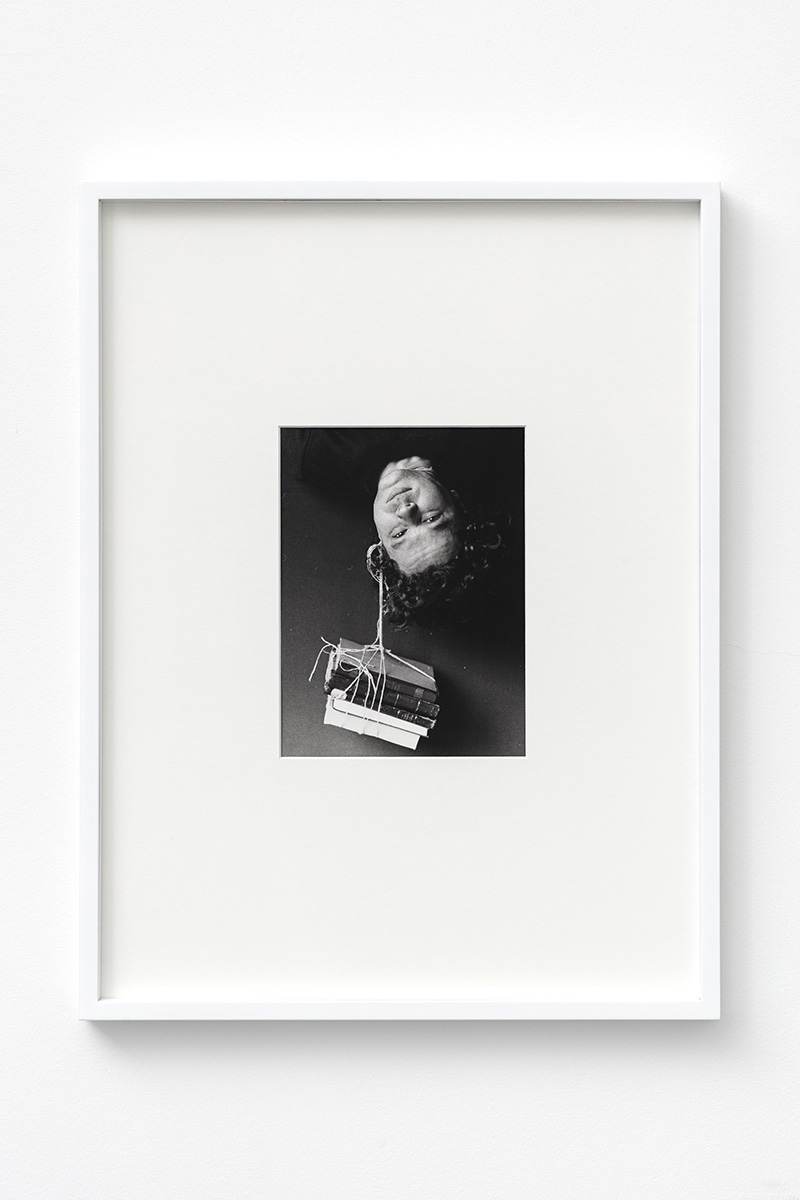

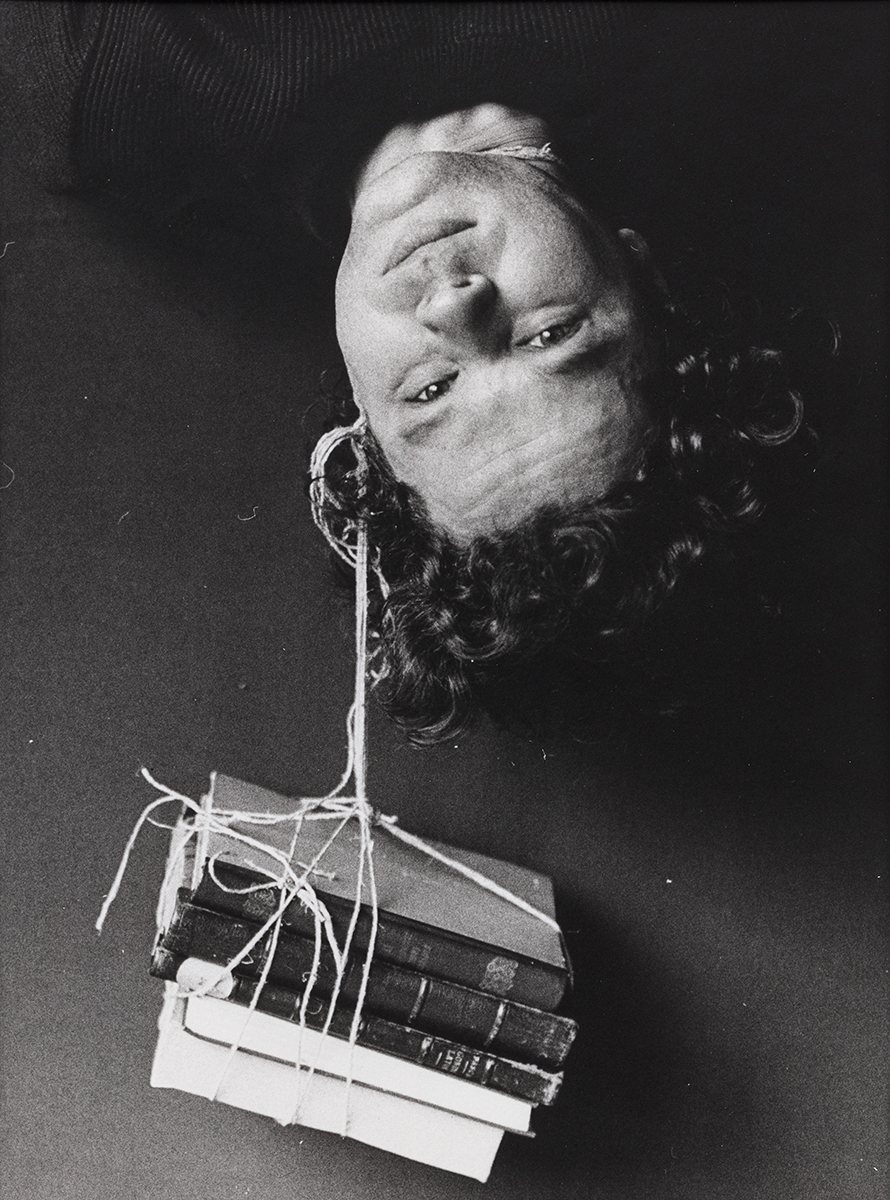

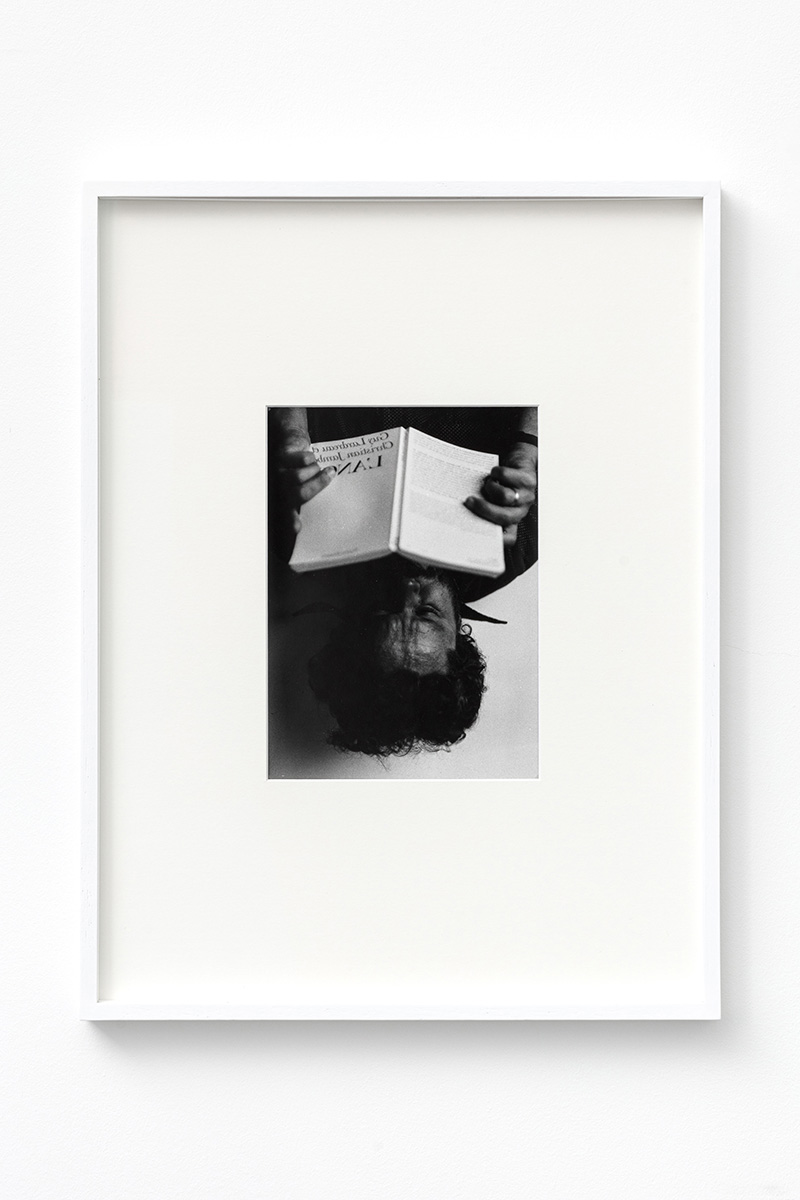

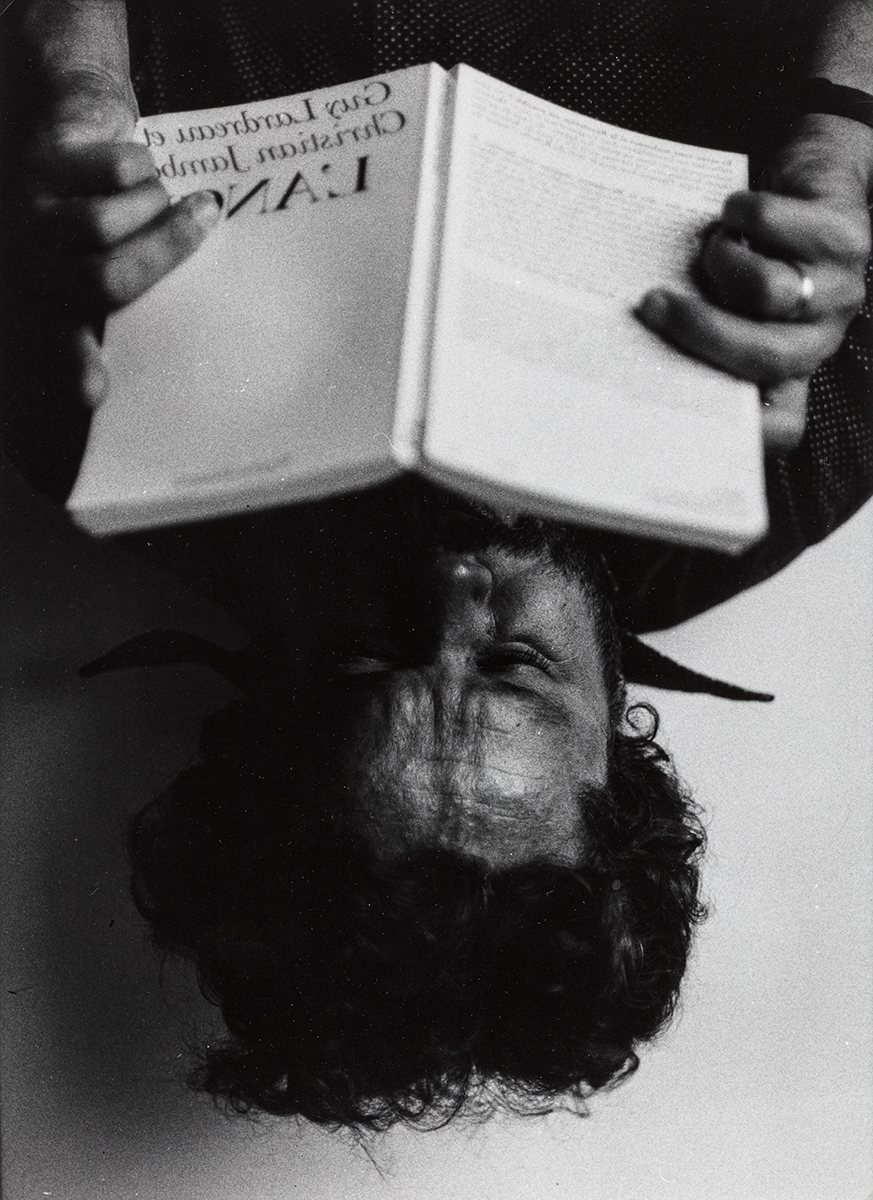

In his conceptual works made in the 1970s, Birkás continued to examine the subject matters, means and timeliness of painting, but with the tools of photography, thus dedicating larger series to painterly self-portraits, portraiture, and the topic of the museum. In case of the three exhibited self-portraits featuring books (The Books I-II., 1978; The Angel, 1978), the artist goes beyond the examination of the painterly portrait: he thematizes the relationship between the text and the image, the interaction between the artist who receipts the texts, and the books. Birkás fastens books – objects filled with ideas and thoughts – tightly around his head, hangs them on a rope tied around his neck, and reads them upside down. The situations involving physical effort show the struggle with theories and the subversive effect of the texts. The only identifiable volume is one of the basic texts of the French “new philosophers” who moved away from left-wing ideas and turned towards metaphysics, a book published in 1976, titled L’Ange. Ontologie de la révolution I [The Angel. The Ontology of Revolution] written by Guy Lardreau – a Maoist philosopher who participated in the 1968 student riots – and his co-author Christian Jambet. Birkás started reading the political and art theory literature acquired from the West in the 1970s with “student enthusiasm”. These self-portraits, which have been kept away of the public for a long time, convey both the need for orientation and the scarce intellectual environment. A closure came with the so-called “anti-textual” series (Night Work – Anti-textual Project, 1978), which put an end to the self-limiting period of the 1970s, as well as the rejection of painting. With large, colourful and expressive pictures, as well as his own writings and lectures reflecting on the changed situation, Birkás joined the boom of new painting at the beginning of the 1980s.

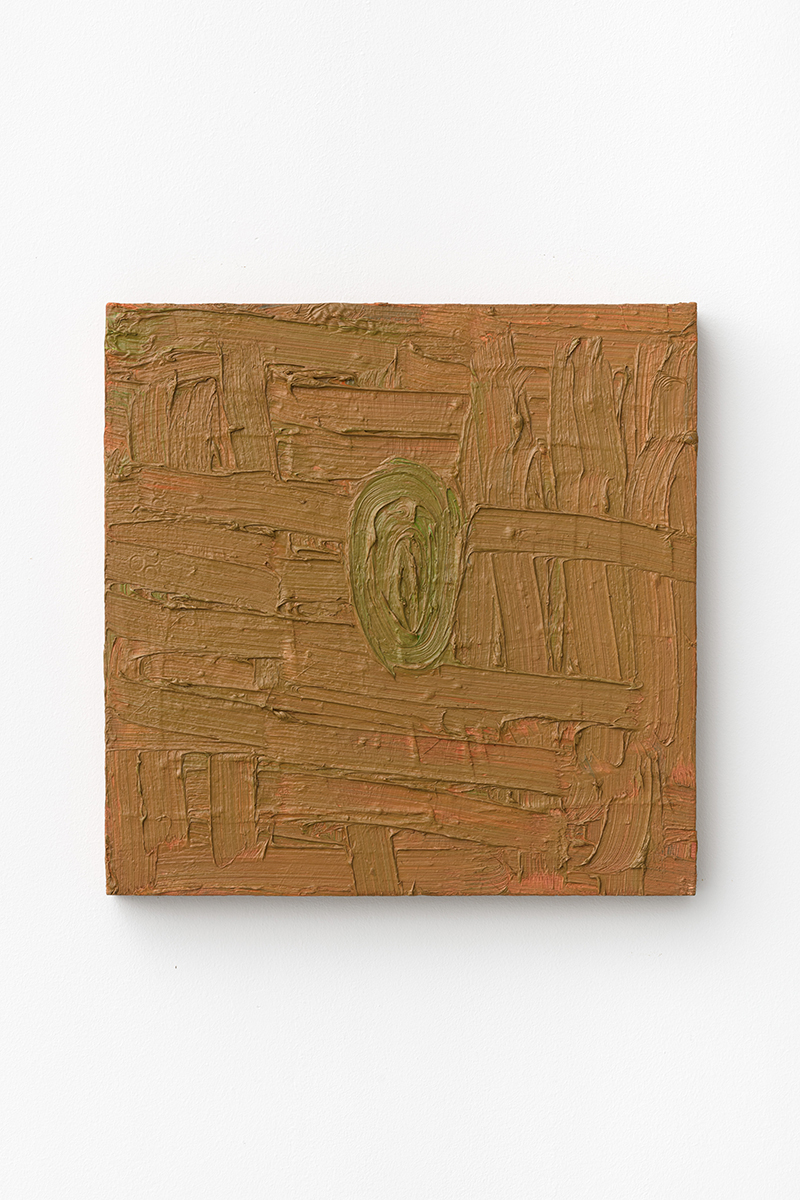

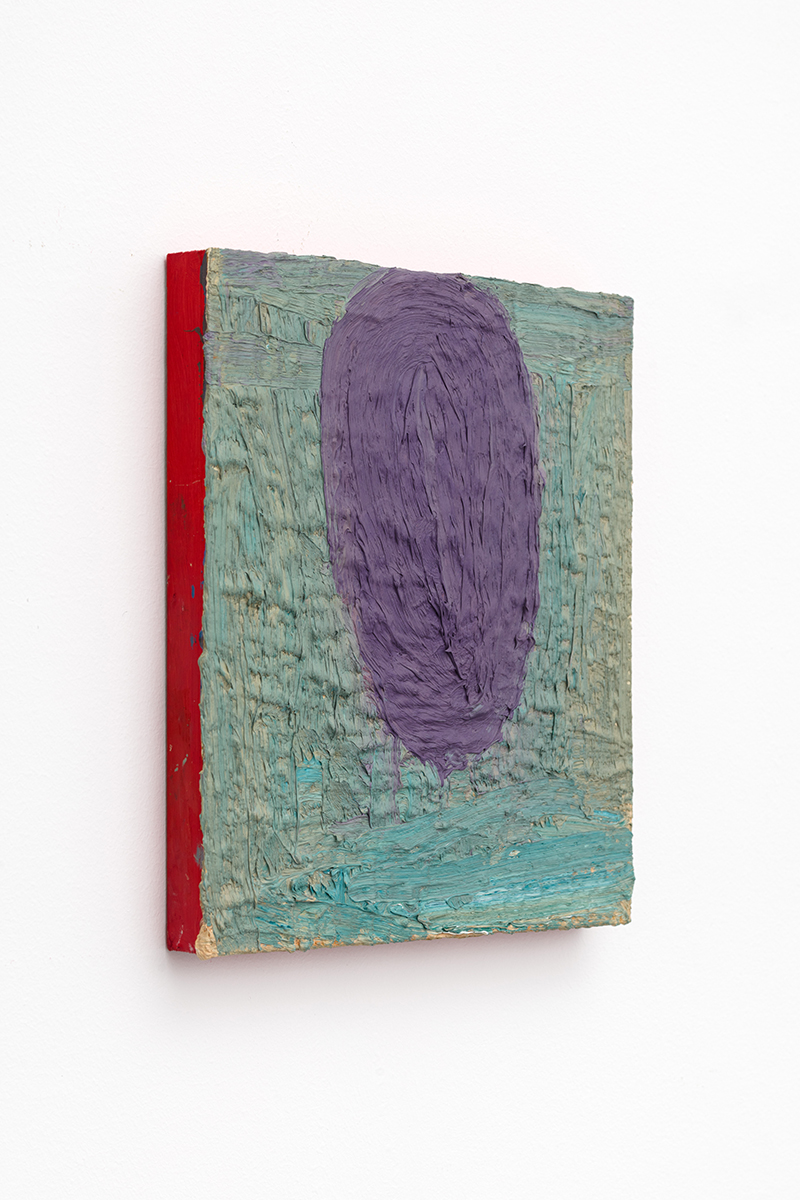

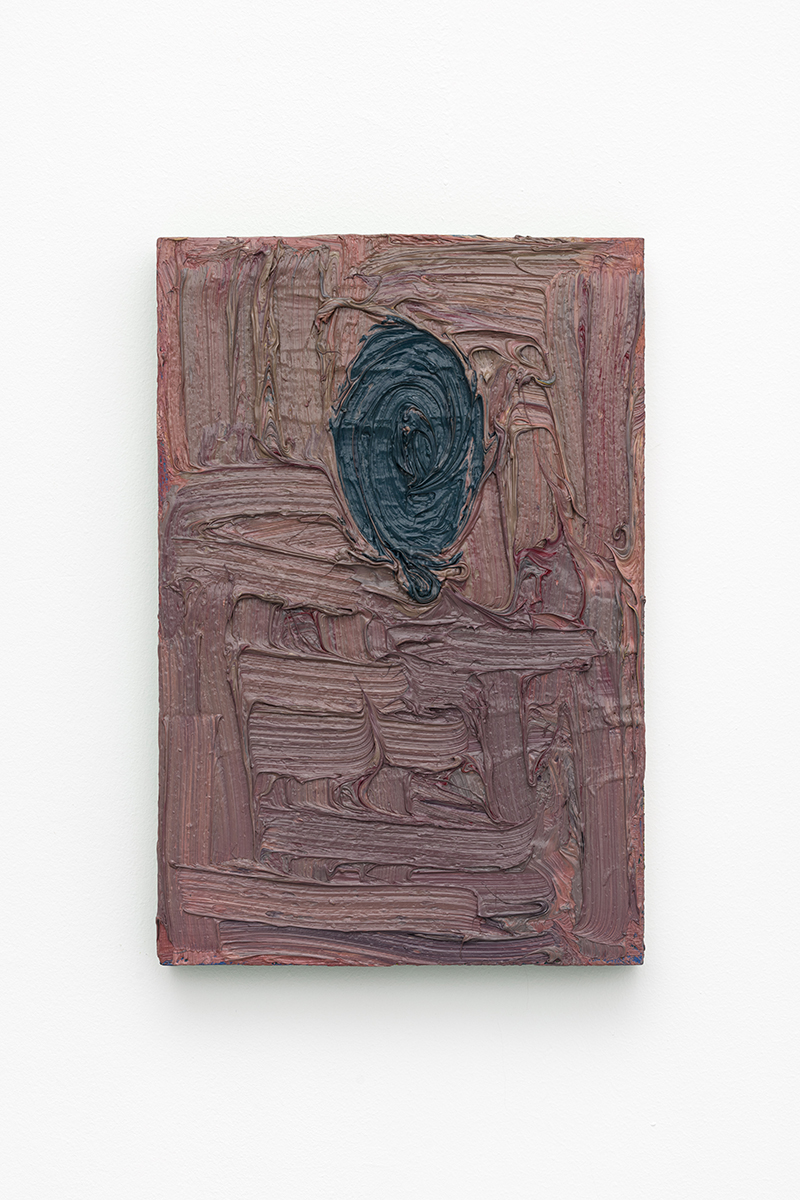

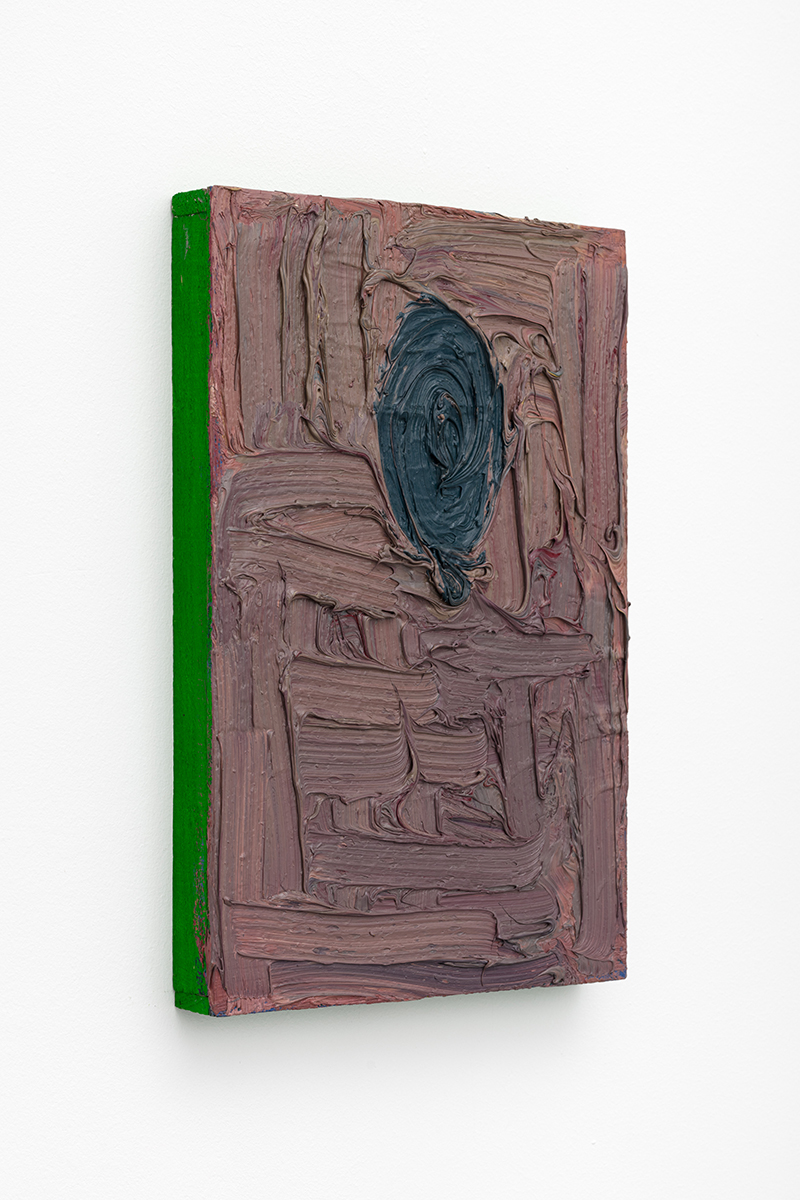

Perhaps the most known works of Ákos Birkás, his abstract, oval “heads” painted systematically from the mid-1980s to the end of the 1990s, are recalled with the help of three small-scale works. From the beginning, Birkás called the oval shape a head, referring to his inherent interest in portraiture. However, the found motif is not merely an icon-like sign or a symbol of a general “self”, not merely a philosophically or existentially demanding condensation. It is a pictorial element that provides an opportunity to investigate painting, painting as the space of the image, so above all the central motif and background, as well as to examine fundamental questions regarding the relationship between the two parts of the image. In case of the “heads” series consisting of more than two hundred pieces, first a reduction, and then an expansion process can be observed. By the end of the first cycle, Birkás reaches a weighty, block-like type of image reduced to a minimum, and then, starting from the 1990s, he gradually dissolves these qualities to reach the limit of possibilities, and ends the series. Birkás’ small heads – just like his watercolours or pencil drawings – are more personal, intimate and sketch-like due to their size, and occasionally more playful. The emphasis is on the relationship between the motif and the background, the “egg” that slides up to the top of the image becomes head-like, and the image itself becomes portrait-like again. The monogram in the title refers to Birkás’ esteemed model, Ferenc Kuppi, and also to the earlier series of portraits of him (KF (71 Bn 6/12), 1996; KF (Mn 8/27) 113, 1998; KF 2An6, 1996).

The critical attitude towards painting and his own art led to radical, yet consistent steps in Birkás’s practice. He received the greatest conspicuousness when he turned again to figurative painting at the end of the 1990s, now incorporating the outcomes of the “technical image” (photograph, press photo, film, etc.) into his art. Between 1999 and 2001, he created a series of double portraits, in which he juxtaposed two different panels, creating a single portrait from the faces of people of different genders and personalities painted with bright colours and light brush strokes. The models are close and dear acquaintances of the artist, but the subject matter remains the relationship between the two halves of the picture: the people looking at the camera, at the painter and the viewer, the opposition or the possible unity of the two faces, the dividing line between the two personalities and the resulting visual and emotional tension, as in this case between the very similar, yet different Anna and Lenke Birkás (O.T. (23.1 A-L), 2001).

Ákos Birkás had his last major exhibition titled The Painters Job in 2014.[1] The title raises banal, yet extremely serious questions that arose from time to time during Birkás’ career as a painter, and resulted in turning points in his artistic practice. What goals can a painter have? What tools can painters use to influence their audience? Does painting have currency in the 21st century, in the age of digital images, unlimited access to press and private photos, and the mass of motion pictures, can it still be an effective means of communication? The paintings made in the last two decades attempt this kind of effective, powerful, and at the same time intellectual communication, with the constant renewal of painterly means and themes.

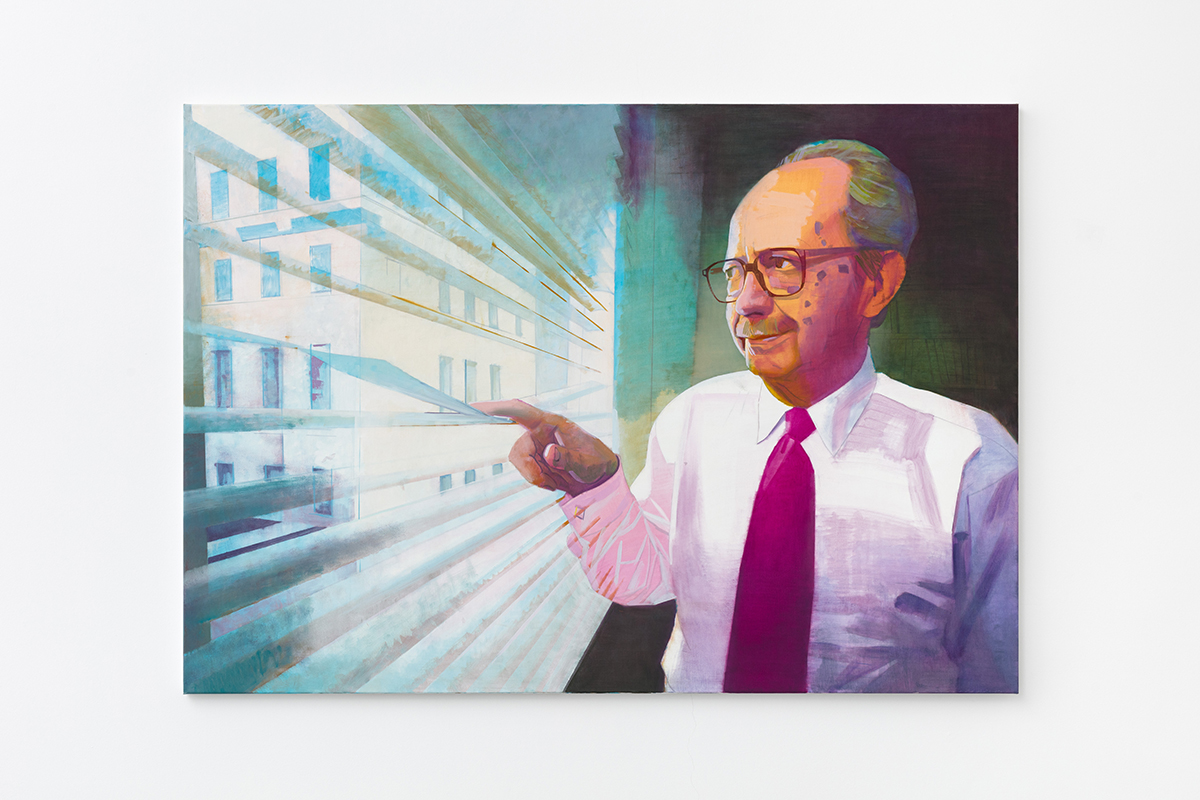

One of the two paintings selected from the 2010s is a portrait of Ralf Dahrendorf (Barricades Close the Street but Open the Way. A German in London, 2010) and a late double self-portrait of Birkás (The Populist Odalisque, 2014). With his paintings based on press photos and his own photographs, Birkás seemingly reflected directly on events taking place in the world, but at the same time, Birkás’ contemplative attitude and observing of the events from a more general point of view can be seen in the selected persons and situations.The relationship between Ralf Dahrendorf and Rudi Dutschke, and 1968 was the theme of Birkás’ exhibition titled “R.D.”, organized at Knoll Gallery Budapest in 2010,[2] where Birkás examined the impact of Western student movements, as well as their delayed and fragmented reception in Hungary through the conflict between the two individuals and the photos, drawings and paintings made of them. Undoubtedly, Dahrendorf’s character and attitude, who in in 1968, as a thinker, intellectual, sociologist and politician testified that “everything that is obvious must be doubted, all authority must be made relative, all the questions that others dare not ask must be asked”, was closer to Birkás, On one side of the sharply divided composition, the contemporary reality of the “street” appears, and on the inner side of the venetian blind, in the interior we see an aging, consolidated intellectual who looks out of the window at the London street in a troubled and pensive manner.

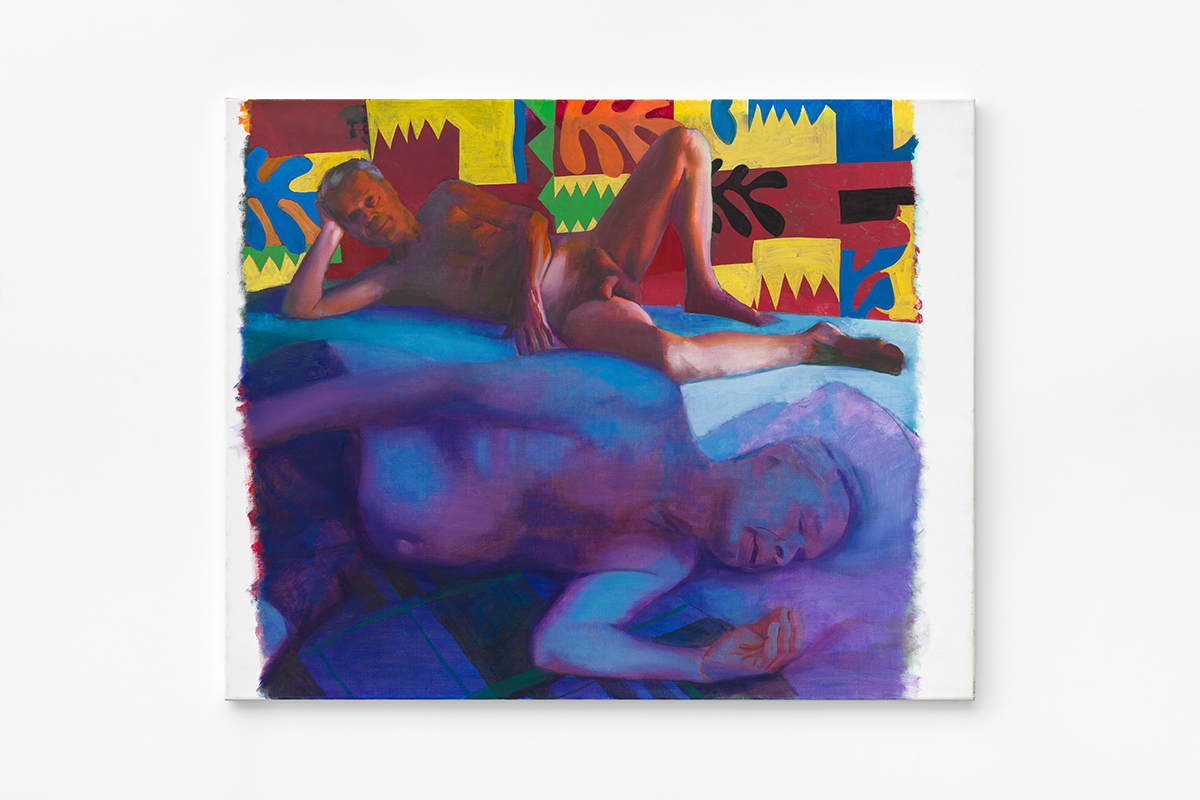

Birkás’ “populist” self-portrait (The Populist Odalisque, 2014) is one of those candid pictures, of which the artist has painted several since 2014, that are not without self-irony, depicting the male body undisguised. In the series, we can see bodies hugging each other in intimate situations, while sleeping, exposed to the viewers gaze and to the camera, often in dark or low light, couples connected to each other in strange situations. In case of the exhibited painting, Birkás appears twice: in the foreground of the picture while sleeping, in bluish night light, and in the background in the pose of Matisse’s famous odalisque, awake, looking at the camera (Odalisque in Red Pants, 1921). The pattern of the background, painted in bright colours, is also reminiscent of Matisse’s late paper cutouts made in the 1940s and 1950s. In his late figurative paintings, Birkás is primarily interested in the concentration and painterly availability of the scenes – the looks, the movements, the general human states of being, emotions, and situations conveyed by them, which rise above the narrowly interpreted reality and daily politics.

Krisztina Szipőcs

The title of the exhibition is a quote from Ákos Birkás. In: Edit Sasvári: Meditative Contemplation. A Conversation with Ákos Birkás. In: Ákos Birkás: Photo Works 1975–78. Knoll Gallery, Budapest, 2012, 56.

[1] The Painters Job. Ákos Birkás (2006-2014). MODEM Centre for Modern and Contemporary Arts, Debrecen, 12 October 2014 – 8 February 2015. Curator: Krisztián Kukla.

[2] Ákos Birkás: “R.D.”. Knoll Gallery, Budapest, 27 November 2010 – 19 March 2011.

Ákos Birkás (1941-2018) visual artist. After completing his studies at the Academy of Fine Arts, Birkás painted expressive portraits and self-portraits in the 1960s, and realistic pictures influenced by conceptual thinking in the early 1970s. From the mid-1970s, he continued his research on the relationship between a work and its environment, a work and its viewer through photography. He was interested in the image as an object and examined roles raised by photography. He returned to painting in 1985 with the abstract Heads, which he later expanded into a monumental series. The only motif of the pictures here is the oval shape enclosed in a rectangle, which allows many possibilities of interpretation. From the 2000s, Birkás turned towards a new direction with realistic paintings that thematize social issues, and from the mid-2010s, he started dealing with the relationship between text and image, abstraction and realism. Self-reflection and questioning the current possibilities of painting are a constantly recurring feature of his artistic practice built upon bold changes. His major solo exhibitions were organized by the Neue Galerie am Landesmuseum Joanneum, Graz (1987); the Slovenská Národná Galéria, Bratislava (1991); the Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien – Museum des 20. Jahrhunderts, Vienna (1996); the Ludwig Museum, Budapest (2006) and MODEM, Debrecen (2014). In addition to his artistic practice, his pedagogical and theoretical work is also significant. His exceptional intellect and open-mindedness also made him known abroad. From the end of the 1980s, he lived and worked in Vienna, Munich, Berlin and Budapest. From 1989, Birkás worked together with Hans Knoll, then from the beginning of the 1990s, he also started working with two other galleries, the Berlin and Leipzig based Eigen+Art, and Zürcher based in Paris and New York. In 2009, the French channel Arte made a portrait film about him (Akos Birkas – Painter, director: Judith du Pasquier). His works can be found in renowned international and Hungarian museums, including the Guggenheim Museum (New York), the MUMOK (Vienna), the Neue Galerie am Landesmuseum Joanneum (Graz), the Neue Galerie (Linz), the Ludwig Museum (Budapest), the Kiscell Museum (Budapest), the Museum of Fine Arts (Budapest), the Hungarian National Gallery (Budapest) and MOCAK (Krakow). He received numerous awards and prizes, his work was awarded with the Herder Prize (1989), he received the Officer’s Cross of the Order of Merit of the Hungarian Republic (2008) and the Prima Primissima Award (2017). In 2007, the Széchenyi Academy of Letters and Arts elected him among its members. After his death, the Birkás Ákos Art Foundation was established in 2019 to take care of his oeuvre.