Dezső Szabó: Copy

2022.02.08 – 03.25.

Can we consider an accidental blot of paint or ink an image? In which state, situation or context do we define this type of sight or stimulus as an image?

The best-known source in the history of European art dealing with this phenomenon can be found in Leonardo da Vinci’s Treatise on Painting (1452–1519). In a chapter titled Rules for the Painter, in the 60th and 66th paragraphs Leonardo states: “Don’t underestimate this idea of mine, which calls to mind that it would not be too much of an effort to pause sometimes to look into these stains on walls, the ashes from the fire, the clouds, the mud, or other similar places. If these are well contemplated, you will find fantastic inventions that awaken the genius of the painter to new inventions, such as compositions of battles, animals, and men, as well as diverse composition of landscapes, and monstrous things, as devils and the like. These will do you well because they will awaken genius with this jumble of things.”[1]

These advices only appear here as spiritual exercises for students who want to acquire the knowledge and skills needed for painting.

Leonardo’s thoughts described above greatly influenced the work of Max Ernst (1891–1976). When creating his artworks, Ernst used, developed and incorporated procedures that operate perception as an active form of art. In 1937, the first issue of Cahiers d ’Art dealt entirely with Max Ernst’s work from 1919 to 1936. Ernst himself described here that Leonardo’s advice on studying spots caused him “unbearable visual obsession”.

During the 20th century, surrealism and abstract tendencies have made the unclear and unobvious perceiving and image-making methods – different from the traditional ways of representation – familiar, or at least accepted.

From our experiences through our senses, our minds are constantly modelling an existing, possible world. What we call an image, more precisely a mental image, is a consequence of the ability that the anthropology of images calls imagination.

Swiss psychiatrist Hermann Rorschach (1884–1922) became famous for inventing the inkblot test named after him. The Rorschach inkblot test is a psychological, diagnostic examination, one of the most commonly used projective tests of the 20th century. Its purpose is to enable the psychologist to map the subject’s personality characteristics in order to supplement other examinations. The test consists of ten plates with symmetrical inkblots. Five inkblots are of black ink, two are of black and red ink, and three are multicoloured. The plates are uniform worldwide, and these figures are among the most famous pictorial symbols in the world. Rorschach’s father worked as a drawing teacher in a private school, and Hermann’s high school nickname was “Klex” (inkblot). There are many assumptions circulating about his nickname and the correlation of the test named after him. At that time, klecksography was commonly played among Swiss children. Ink was dropped on a piece of paper, which was then folded in half, so the blot formed a butterfly, a bird, etc.

Pareidolia is a tendency for perception in which we feel uncertain and random stimuli, sounds or images, specific and clearly discernible. Pareidolia is a subtype of apophenia, which is considered to be a general impact of brain activity. In extreme cases, it can be a symptom of psychiatric disorders.

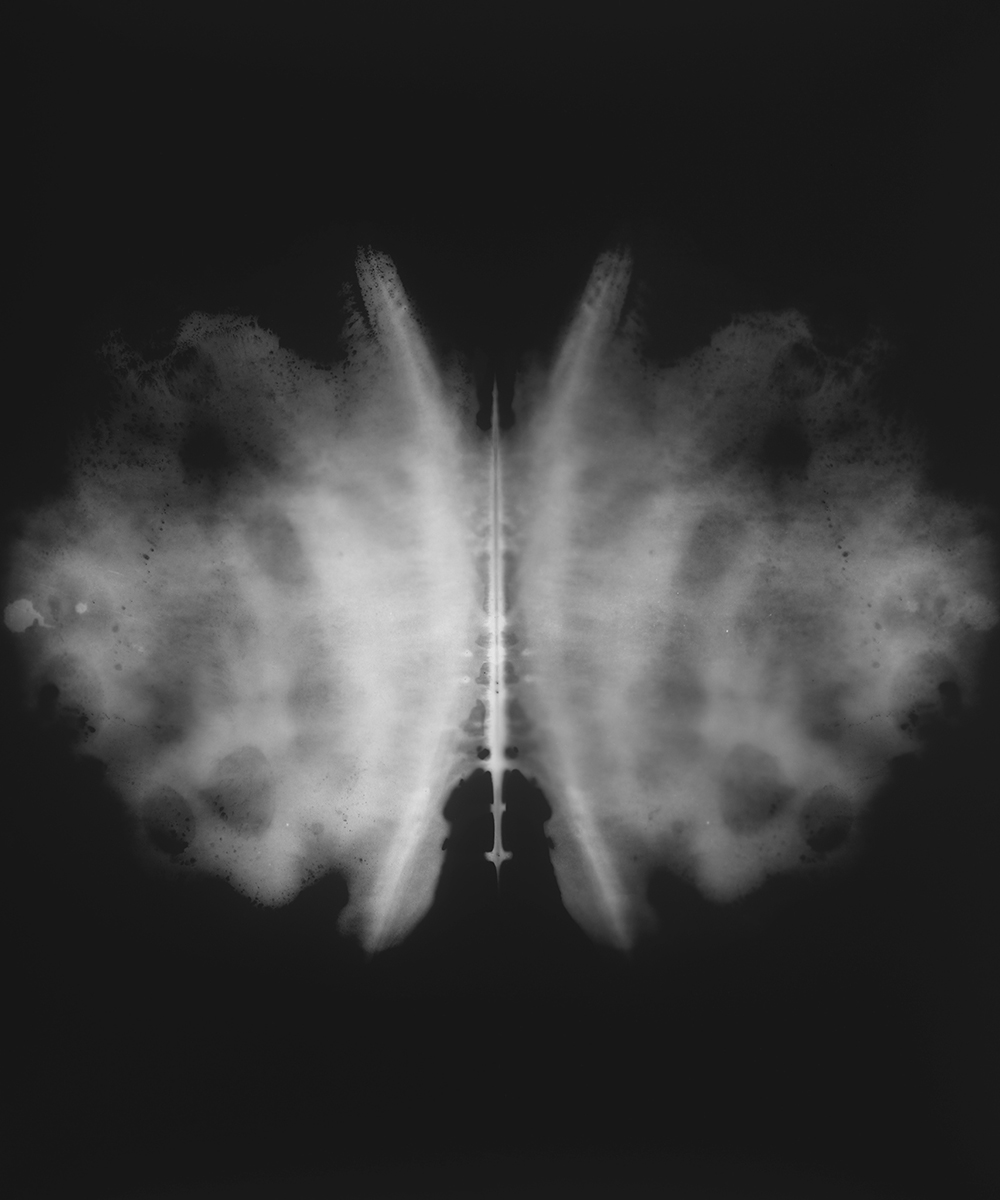

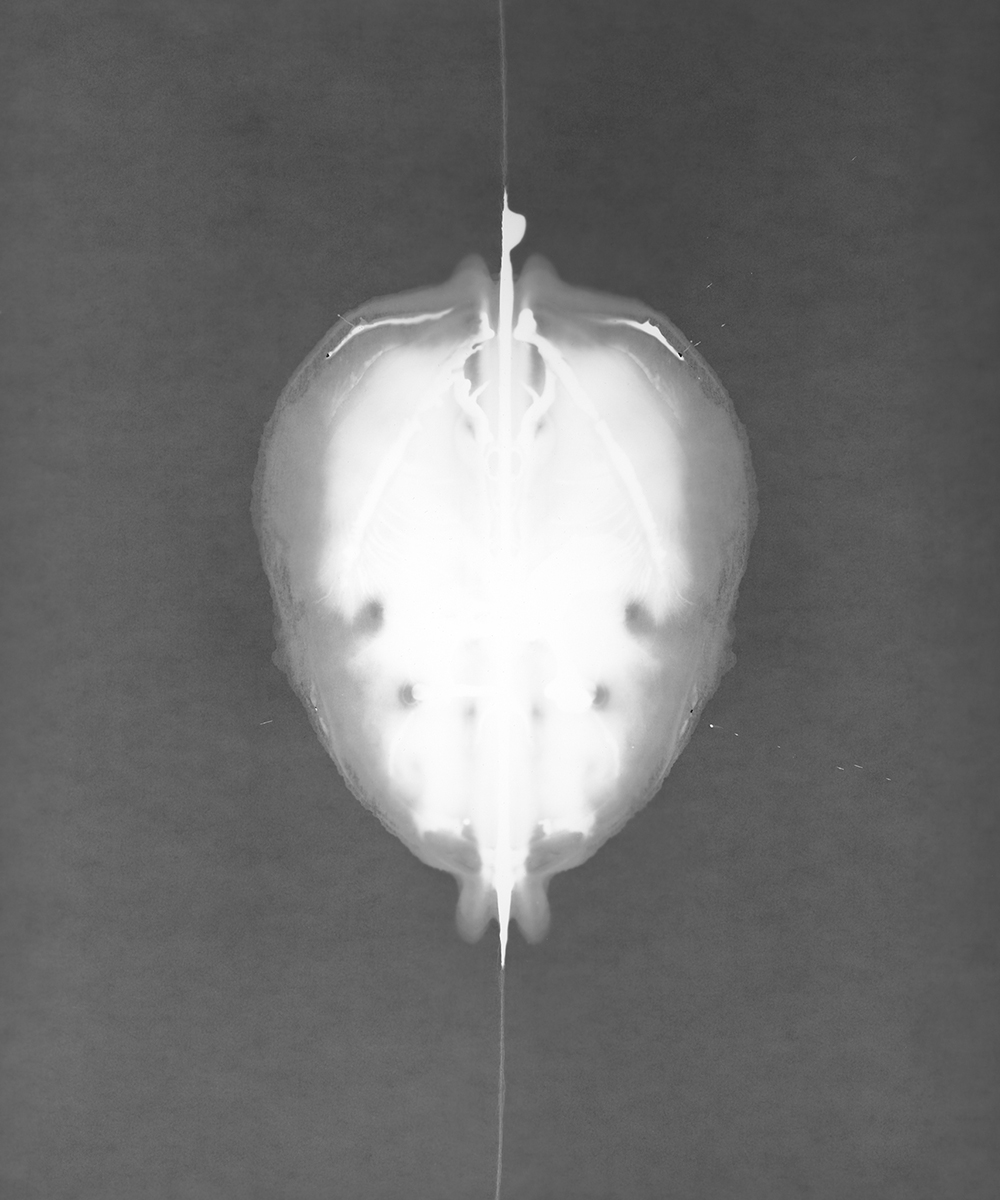

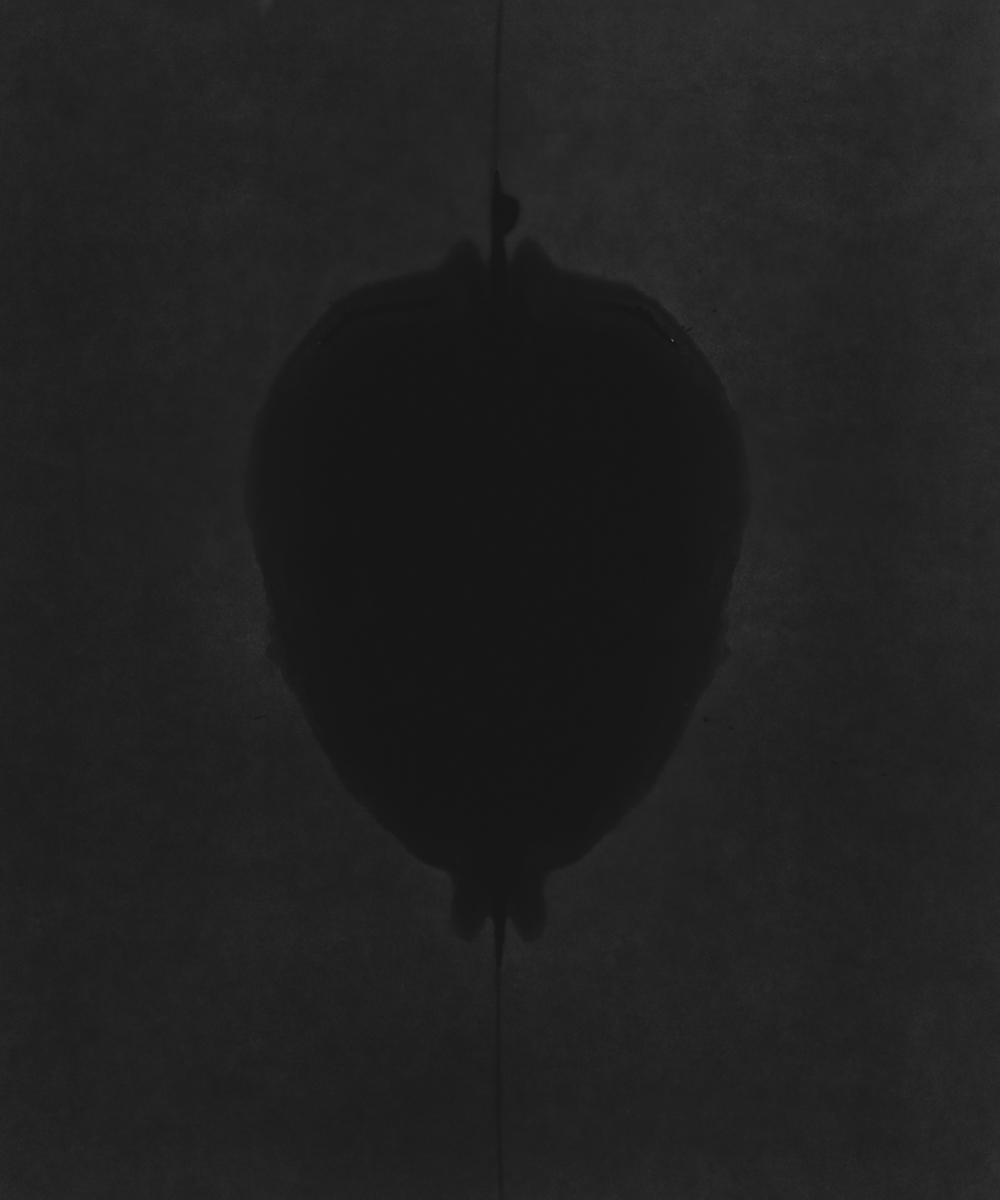

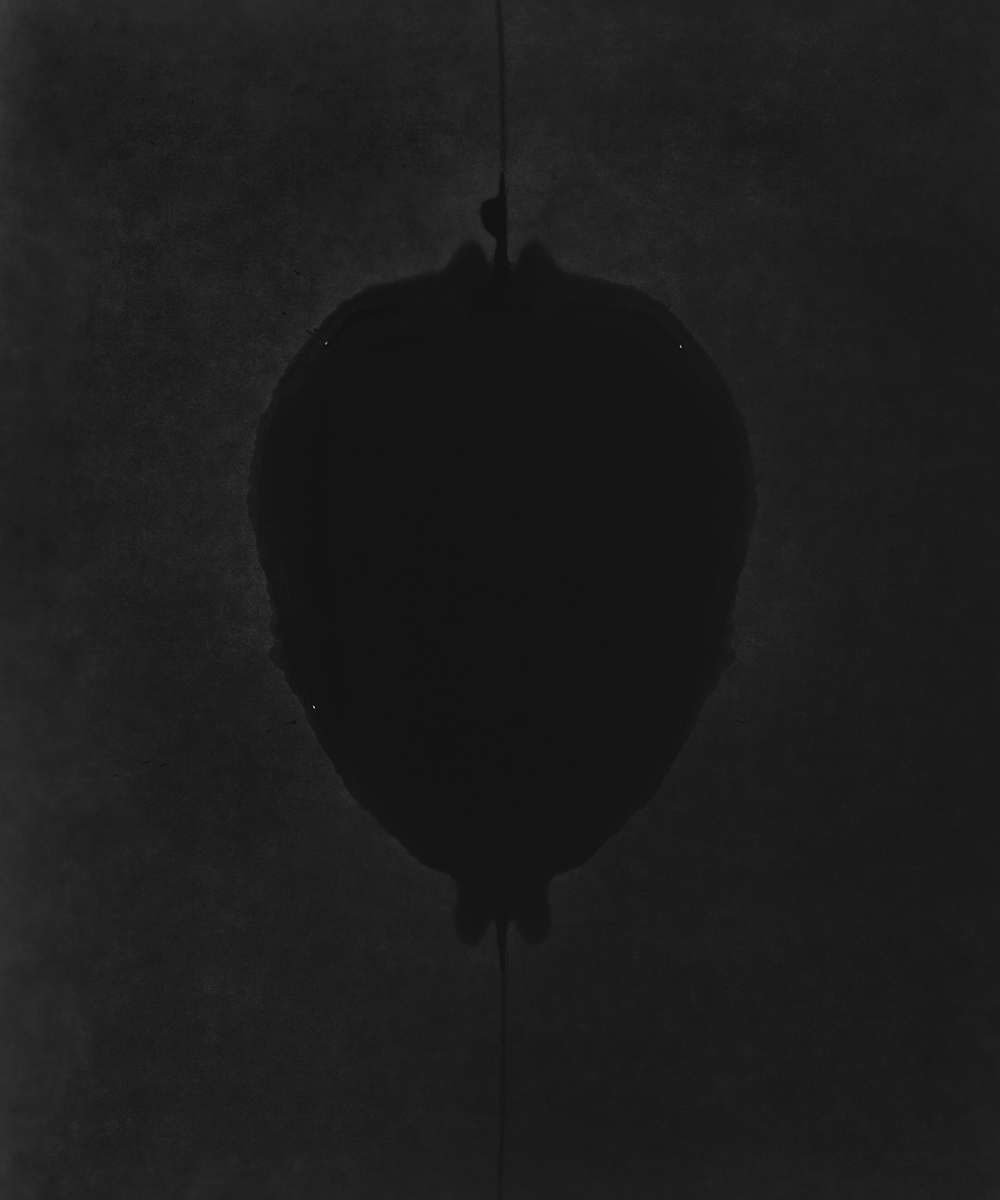

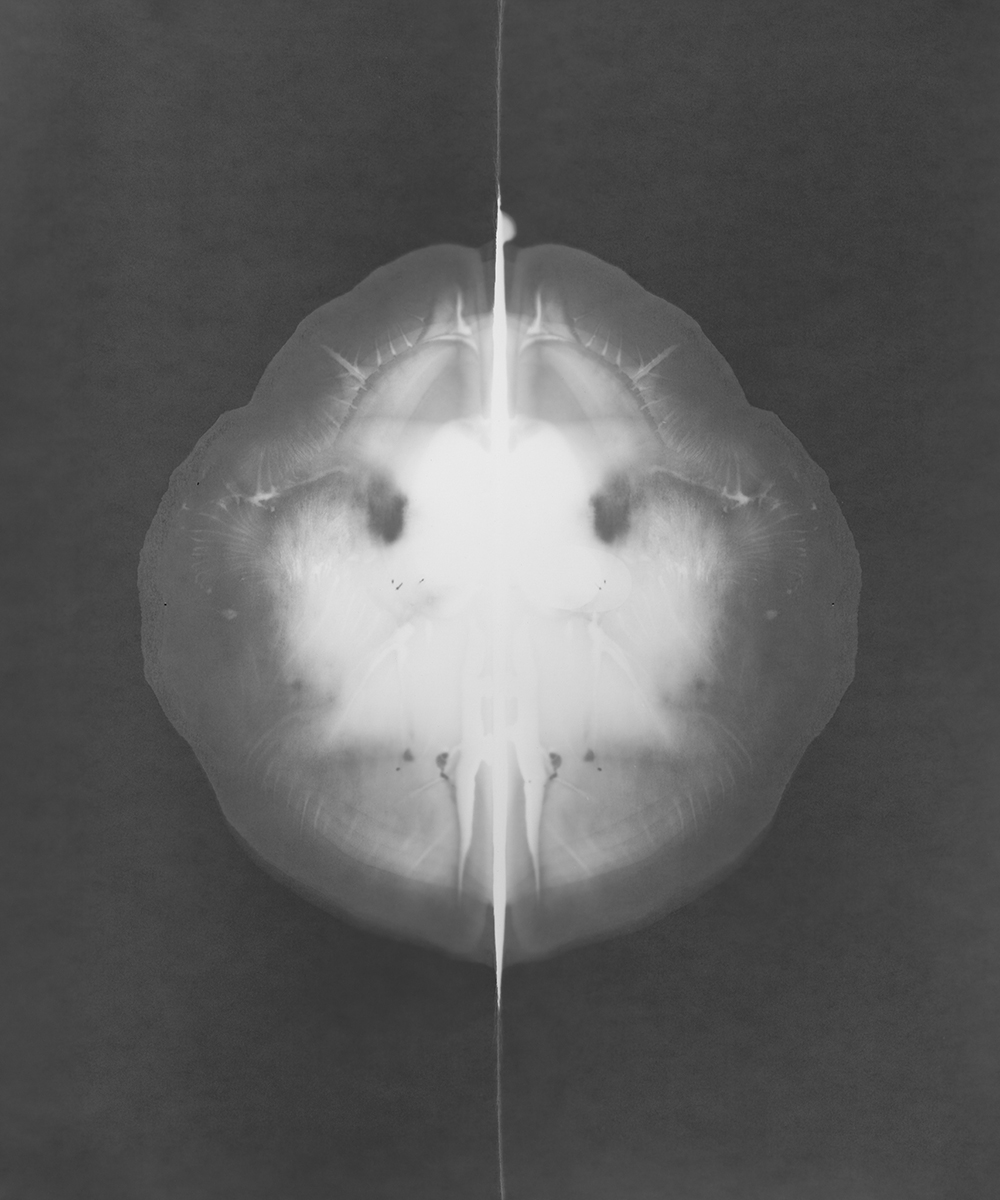

The series titled Copy can be interpreted within the field of cameraless photography, and was created using the chemigram technique. The visual representation of the concept of the copy is realized based on the physicochemical properties of the black and white photo paper. First, the unique object-nature of the photo paper is decisive, as it is a sheet of paper that can be shaped, and in this case folded. Secondarily, it can capture and store light as information. These two qualities together formed the concept of making the series.

Copies here are not created using negatives on which images were optically projected (they are not photographicprints of negatives on paper), nor is the image created by the negative light imprint of a foreign object (the initial image is not a photogram). The forms are created by only using the developing and fixing solutions, the light and as a defining, unique element, the folding of the photo paper. This is a kind of special monotype method, self-copying. The resulting shapes are similar to the figures in the Rorschach test.

The simplified technical description of the creating process of the work is as follows: developing or fixing solutions are dripped on the photo paper, which was previously folded in half along its vertical axis and then unfolded. Thereafter the paper is folded and unfolded again, then it gets exposed to light. Dark blots are formed on areas affected by the developing solution, and then the paper is immersed in a fixing bath. If a blot is made with fixing solution, the affected area cannot develop, so it remains white. The paper goes into the fixing bath, and a white figure is created on a black background. The image is then fixed according to the common process to make it permanent. Using the traits of the black-and-white process, a black shape on a white background or a white shape on a black background can be obtained.

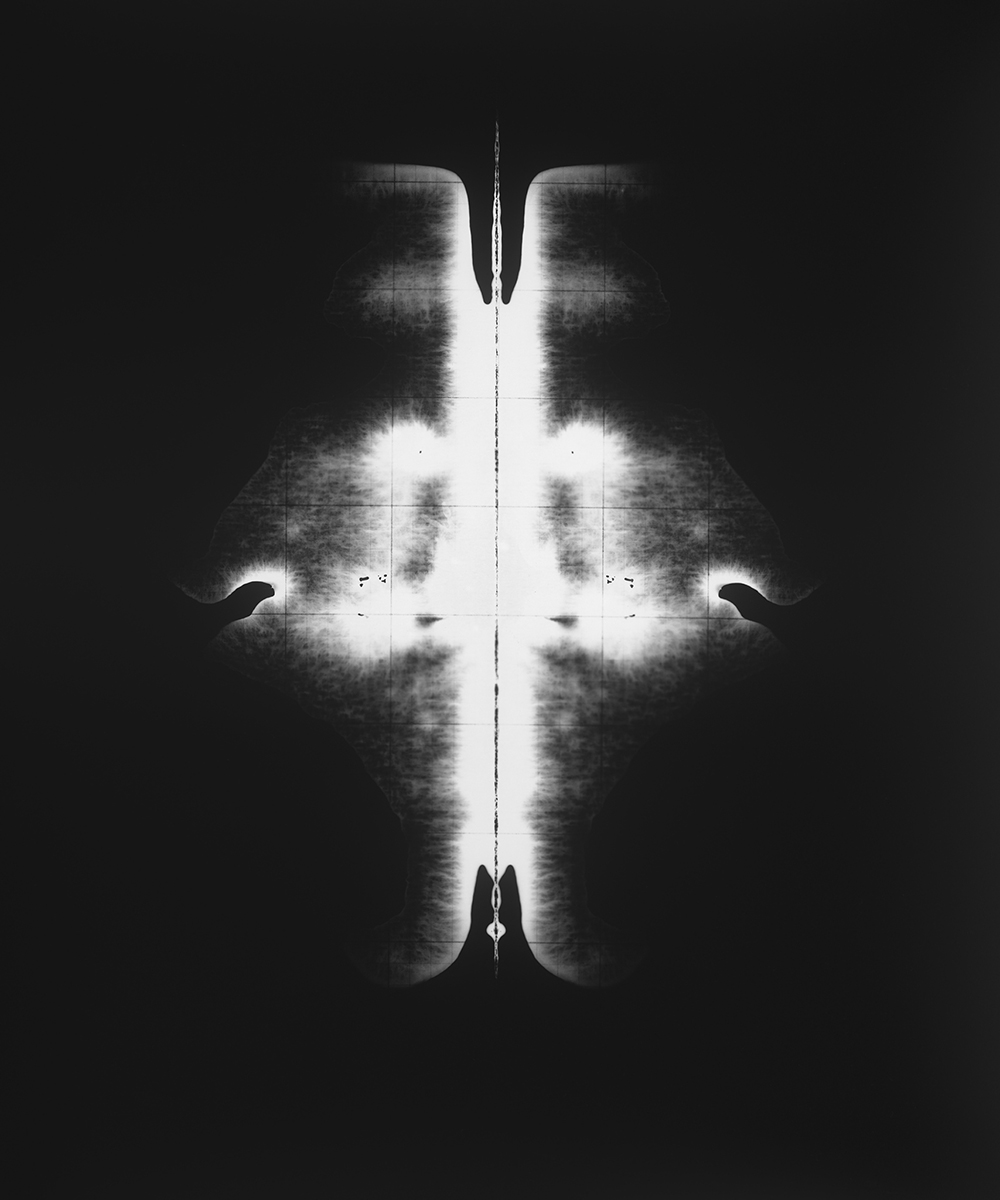

The right and left sides of the resulting blots are simultaneously arising – although not completely identical – copies of each other due to the method. The initially created image can even be called original. In this procedure, the use of photo paper may go beyond the meaning and the possibilities of an artistic process created with paint or ink.

Moving forward, using the initial image (original) as a paper negative, it can be copied by contact printing, in which case we get the photographic negative of the original form. The shape can be oriented identical or mirror symmetric. Using the copy in a subsequent copy can also create an image that is just alike (or very similar to) the original. In this way, the abstract blots, the practicable procedures, and the possibilities of the variations form a system. They demonstrate the visual and photographic logic of self-copying, repetition, mirroring, copying or reproduction.

The realized series was not intended to present all of the possibilities that follow from those summarized above. Theseinstances are the basic constituents of the visual language, and the possibilities could only be articulated in a number of new series.

In addition to the two triptychs and one diptych, the Copy series consists of 18 individual images. The diptych and thesolo pieces are based on symmetrical blots. Some of them are “original”, while others are “copies”. For the visual effect, and as well as for uniformity, the entire series – with the exception of a single image – consists of white shapes on a black background. These works can be mostly associated with the visuality of medical imaging (X-ray, ultrasound, CT, MRI, PET). The two main reasons are that they are predominantly black and white, and because of their symmetry, the blots themselves are reminiscent of the structure of some sort of biological organism. The two triptychs were created with the chemical imprint of circular forms, both carrying an approach of the visual-logical system of repetition.

Dezső Szabó

[1] In: Leonardo da Vinci: Treatise on Painting (translated by John Francis Rigaud).Dover Publications, New York, 2005.

“Does it create something unitary or something dispersed? Auratic or serial? Similar or different? Identical or unidentifiable? A decision or a coincidence? A form or something unformed? The same or something different? Familiar or unfamiliar? A contact or a distance?” – asked Georges Didi-Huberman dissecting the procedure of imprinting in his book titled La Ressemblance Par Contact.[2]

These questions can also be raised in connection with Dezső Szabó’s series titled Copy (2021). The works exhibited in Vintage Galéria were created using the chemigram technique, as Szabó dripped developing or fixing solutions on the surface of the photo paper, then folded the paper in half, thus obtaining a symmetrical blot. Using these initial images as paper negatives, he also occasionally created contact prints.[3] The works can be considered only copies in a degraded way, as the artist reduced the abstract pictorial element created in a photographic process to the level of an imprint by folding the photo paper, and the picture to the status of a copy through the self-copying and contact printing procedures. But isn’t it time to go beyond our established notions of the relationship between the original and the copy?

It is a series of statements on the status of artworks and experimentation at the same time, as the prints reproduced through contact create a unique sequence or a network of interactions between substances. To make this intertwined structure visible, through an extended examination of the materials Szabó questions everything we know so far about the chemicals used, the paper and the process, and ultimately the image itself.

The method of creating the series thus carries the complementary meaning of the French term “expérience”, as it also bears epistemological connotations beyond the physical experimentation. However, the creating process slips out of the artist’s control as the metamorphosis of the blots takes place inside the structure of the folded paper, activating the mechanisms of the “technological unconscious”. The evolution of the shapes remains inaccessible to the artist’s consciousness and associations until the paper is unfolded. Following the revelation of the shapes, visual memory comes into play, searching for similarities between the forms that has become visible and the forms preserved in memory, which metaphorically can be called engrams or imprinted memories. This situation – just as the case of the Rorschach test[4] – can evoke a particular “conscious awareness” in which the viewers are cognizant of the fact that the blots have no definite meaning and are depending on interpretation.[5]

However, the proper perception of the works is only possible if we can trace back the principles of the creating process and think of the questions raised in a broader context. This is how we take over the working mechanism of the series: we experiment. Or as Didi-Huberman states: “It’s a refined game that we can only conceive of with a binary approach: first, with a particular look (focusing on the procedure), then looking for extended aspects (concentrating on paradigms).”[6]

Zsófia Rátkai

[2] Translated from Hungarian. In: Georges Didi-Huberman: Hasonlóság és érintkezés – A lenyomat archeológiája, anakronizmusa és modernsége(transl. Nikoletta Házas, Tamás Moldvay, Tamás Seregi, Zoltán Z. Varga). Budapesti Kommunikációs és Üzleti Főiskola, Budapest, 2014, 15. I used Didi-Huberman’s insights on imprints throughout the whole text.

[3] See the more detailed technical description of the creating process in Dezső Szabó’s text.

[4] See the more detailed description of the Rorschach test in Dezső Szabó’s text.

[5] Ferenc Mérei: A Rorschach-próba. Medicina, Budapest, 2002, 81-82.

[6] Didi-Huberman, 2014, 122.

Dezső Szabó (1967) visual artist. Between 1990-97, Szabó studied at the Painting Faculty of the Hungarian Academy of Fine Arts. After his initial engagement with monochrome painting, he became interested in photographic image making. During his early period, he captured scenes modelled from still photos extracted from television programmes of air and natural disasters (black box, 1999), various natural phenomena (Tornado, 2001), enigmatic locations (Spot, 2000), and deep-sea photography on his small film camera. In his series titled Time Bomb (2008), the self-destructive logic of the mock-up approach and the chosen subject matter signified an extreme endpoint in his modelling of visual scenes. In recreating the scene and the image, Szabó was already questioning the operational mechanisms of images and their contemporary status during this early period. As of 2015, he extended his activities to exploring the nature of analogue photographic images. Dezső Szabó’s works have been featured at numerous solo and group exhibitions; his latest institutional exhibition titled Darkroom was held in 2018 at the Hungarian Museum of Photography. His works can be found in the collections of the following prominent institutions, among others: Hungarian National Gallery (Budapest), Ludwig Museum – Museum of Contemporary Art (Budapest), Institute of Contemporary Art (Dunaújváros), Art Gallery Paks (Paks), Rómer Flóris Museum of Art and History (Győr), and Hungarian Museum of Photography (Kecskemét).